Logan was adopted 11 years ago. At the end of 2012, he arrived in the United States with his adoptive parents Julie and Robert Vilardo. Four siblings were waiting for him at his forever home in Ohio.

In the spring of 2012, Maya’s Hope initiated a “Guardian Angel” program dedicated to providing caregivers to orphans residing in one institution called “Kalinovka” in Zaporizhzhia region. This is where Logan was. In May of that year, Julie reached out to Maya’s Hope with the message:

“We are interested in helping the kids at Kalinovka. If all goes well we hope to bring a child home from there. While we wait, how can we help?”

Julie subsequently became the second sponsor of the “Guardian Angel” program. Her sponsorship covered the entire salary of an additional caregiver for orphans at Kalinovka.

We spoke with Julie about the journey of adopting Logan, his unique condition, and the misconceptions surrounding the international adoption of children with disabilities.

Interviewer: How did you find Logan? How did his American story begin?

Julie: I have three biological kids. They are older. We adopted a girl from Kazakhstan. Through her adoption, we found an organization called Reece’s Rainbow that advocates for children with special needs. On the pages of their website, they list orphans with Down syndrome and other special needs who are on the search for a forever family. So, we were looking through the pages of the website more out of curiosity rather than the intention of adopting a child. We felt that God would call us to adopt when we come across our child. One day, after a while, we saw a photo of Alex (the name Logan was listed under on Reece’s Rainbow), and it was almost audible, “This is your child, this is the child you’re supposed to adopt.”

Interviewer: Logan has phocomelia (a rare birth condition that causes the upper or lower limbs of the child to be underdeveloped or missing). Did his condition frighten you?

Julie: We were looking to adopt a child with a condition like that. But we imagined it would be a child with a missing arm OR a missing leg. When I saw Logan, I thought it would be more than I could take on. I shared that with my husband, and he felt the same way. We already had four kids. So we started inquiring about other children, but as soon as we sent an inquiry, the door to their adoption would instantly close. It felt like God was saying, “I told you, I showed you the child you should adopt, so quit being stubborn.” And we started right off the bat with Logan’s adoption process.

Interviewer: Did you face any challenges with international adoption?

Julie: We started the adoption process in May 2012. In June of that year, the BBC’s documentary “Ukraine’s Forgotten Children” was released. In the fall of 2012, Ukraine hosted the UEFA European Football Championship. In August 2012, my oldest son broke his neck, and we were in California for his surgery. We had a lot going on. But I was confident that we would be fine, we would not have to go to Ukraine in the fall during the football season because international adoptions take years. And while we were in California, I got a call that said, “Be in Ukraine in two weeks.” And I said, “Okay, hold on a minute.” (Laughs)

Interviewer: So you traveled to Ukraine. Did you have any challenges in the country during the adoption process?

Julie: Besides traveling to Ukraine during the heat of the football season, the only challenge was that Logan’s orphanage* was pretty remote. Because of the documentary, I had a general idea of what the orphanage was like. But I didn’t realize how remote it was. So, Robert (interviewer’s note: Julie’s husband) and I flew over to sign the paperwork. We landed in Kyiv, then hopped on a train and had a 12-hour train ride, signed the papers. And then Robert had to turn around right away and go back to the airport, which took another 12-hour train ride. He went back to the airport, and I was left at the orphanage. And I lived at the orphanage for five weeks, which was a challenge in itself.

Interviewer: It is not very common for an orphanage in Ukraine to let an outsider stay there…

Julie: They recognized my tough situation. I had two choices. I could either live in the closest city, which is about two hours away, and they would come to get me once a week to go visit them, or I could live on the orphanage’s territory. The orphanage had an apartment building where the workers lived, and I could live in one of those apartments. So, I stayed. I had to go to the well, draw out the water, and then I would boil it in a teapot, then I would put it into a liter bottle. And I would take three of those, stand in a bucket, put a bottle over my head, and that was my shower. I mean, there was no running water in the apartment. I had to go to the outhouse to use the bathroom. And I had no Internet and no cell service for a week or so, which was probably a good thing with the way things went to start with. There was no getting out of our decision. So, for 5 weeks I lived like all of them and ate what everybody ate, what the orphans ate.

Interviewer: Did you eat together with them?

Julie: They served me in a different building and dining room than the orphans. And I had set times that I could come to visit. That was between 9:00 am and 11:00 am and 2:00 pm and 4:00 pm. And the rest of the time I was hanging out by myself in an apartment with no running water.

Interviewer: And with no communication with the outside world?

Julie: With very limited. When we adopted our daughter from Kazakhstan, I learned enough Russian that I could get by a little bit. After a week, I finally got our facilitator to come take me to the city. And I bought a Ukrainian phone and paid for minutes to have Internet. After a week, I got some service. But initially, it was a challenge.

Interviewer: How did you communicate with Logan, with other orphans? Did you know enough Russian to be able to talk with them?

Julie: No, because honestly, most of the kids did not speak either Russian or Ukrainian. They spoke in their own “orphanage language.” When we adopted Logan and brought him home to the US, our local children’s hospital provided translators for him. They provided a Ukrainian translator, but that didn’t work. Then they provided a Russian translator, and that didn’t work either. He literally had what I referred to as his own language, which was the way they spoke at the orphanage. He had made up words that he would use for things. And the translators here could not figure it out. But at the orphanage, my Russian worked, and honestly, we got by a lot with just pointing and gesturing.

Interviewer: How long did it take Logan to learn English upon his arrival to the United States?

Julie: I think he picked it up pretty quickly. Both of my adopted children could understand it, and it depends on what level you refer to. After six weeks, I feel like we could communicate okay. But Logan’s speech was delayed in general. For the first three years, one of his school goals was to say more than two or three words at a time. He could explain what he wanted in separate words such as water or food, but he couldn’t really carry on a conversation. And he can carry on a full-on conversation at this point.

Interviewer: Does he remember Ukrainian or Russian, or that mix of languages that he spoke before?

Julie: Probably only words that he shouldn’t remember. He has some words for his sisters that I don’t think he should be saying, but I don’t know what they mean. And I’ve asked a few people, and they don’t know what they mean either, but I suspect they’re probably not good words. (Laughs) I have a Russian-speaking employee from Chechnya. When she comes into the office, she’ll say hi to him and ask him how he’s doing in Russian. He understands that. He remembers some very basic terms.

Interviewer: I saw some photos of Logan walking using prosthetic legs. How fast was his physical development after he arrived in the US?

Julie: Logan started using prosthetic legs 10 years ago. He made huge improvements and learned to walk, but this February we decided to go away from doing it. Because of the time he spent in an orphanage bed, his stamina and his hips are not developed properly to functionally walk. The amount of energy it took him to walk was too much, and the speed at which he could walk was too slow. We would go to therapy every weekend. He had a therapist he loved who did an amazing job with him, but then he closed his office. We faced the necessity to start over with someone new. Initially, we pushed for prosthetic legs because he had scoliosis that potentially required full spinal surgery. After that surgery, he would lose his ability to use his arm at all. Right now, he can reach things by picking them up between his chin and his shoulder. But to do that, he must lean sideways. If we rodded his back, then he wasn’t going to be able to ever get around the way that he does. And the prosthetic legs were supposed to be the backup plan when the surgery happened for his back. But we decided not to do the surgery on his back because of these complications. We don’t want him to lose his freedom. There is a video of Logan putting the desk together. I had a new employee in the office, and Logan put together a desk for her pretty much by himself. Choosing surgery would take away his ability to do things like that.

Interviewer: What does Logan do now?

Julie: He works at my dental office as a paper shredder. He also watches security cameras for us. He’s even caught a few people trying to break into cars before. He loves this type of work. Logan is, technically, a police deputy in two different counties. They’ve just sworn him in.

Interviewer: Have you encountered any misconceptions or stigmas about adopting children with disabilities from overseas?

Julie: Unfortunately, a lot of people don’t understand it. We’ve heard people saying that we were ruining our lives and encouraging us not to do it. And there are still a lot of people who look at Logan and think that he’s not as capable. That’s why I try and video him doing different things. So, when they look at him and feel sorry for him, I’m like, hey, check out this desk that he built. And then it changes the whole perspective. If you have a child with a disability, it’s often thought of as a burden. And a lot of people don’t understand the love that you feel for the child and the love you get back in return. Honestly, of my five kids, he’s the absolute easiest. Developmentally, he’s probably a seven- or eight-year-old. He’s not an adult or demanding teenager. He’s super, super loving. And he’s always happy.

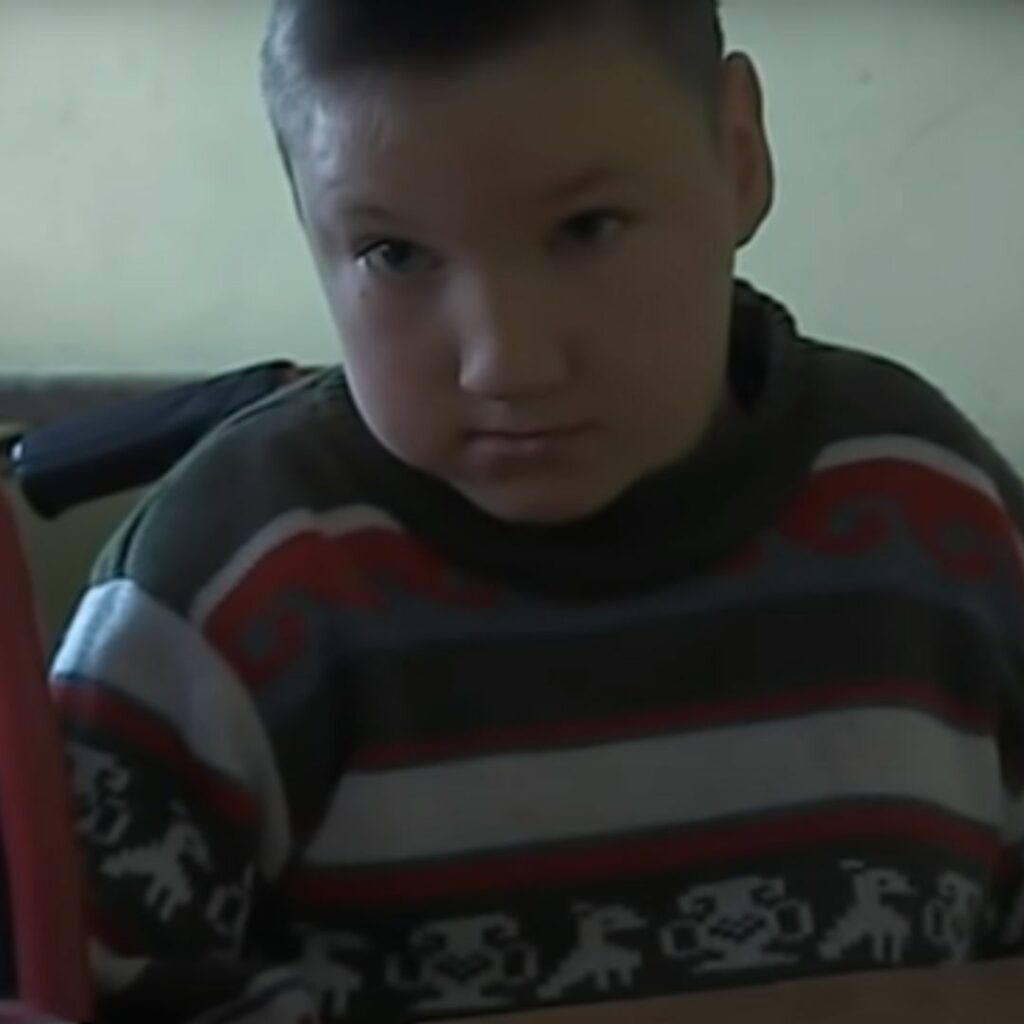

Interviewer: When I watched the documentary, I noticed that even then he radiated that positivity that you usually don’t see in children from institutions and orphanages. He smiled like there were no challenges in his life. He looked like a very happy person.

Julie: And he is still this way. That’s amazing.

Interviewer: Does he ever talk about Ukraine and those days when he was in the orphanage or his friends from the orphanage?

Julie: We talk about the friends from the orphanage on a regular basis. And Logan actually watches that documentary a lot. From the group of nine shown in the documentary, several were adopted. With a few of them, we had a chance to get together in the U.S. and even had a playdate once. We just learned that one of his friends from the orphanage passed away. And we talked about it as well. Does he talk about life in the orphanage? Not so much, other than saying he doesn’t want to ever go back to the orphanage. “No dom, no dom” (interviewer’s note: this means “no detdom” which translates to “no orphanage”). He doesn’t want to go back to the “dom”. And sometimes if he gets nervous, he’ll start saying, “I get to stay with mama all the time, right? No more dom, right?” He still needs reassurance. Not often, but every once in a while, he wants to make sure that he’s not going back.

Interviewer: Was he mistreated there?

Julie: He doesn’t talk about being treated badly. When we can get him to verbalize why he didn’t like the orphanage, he says, “I didn’t get to drink coffee.” He’s a big coffee drinker now. And in the orphanage, he got to only drink tea or cocoa. That’s his only complaint. This might be his way of saying that they didn’t have the freedom that he has right now. But it’s such a sweet way of putting it.

Interviewer: From your experience as an adoptive parent of children from overseas and with disabilities, what would be advice that you can give to families looking to have the same experience?

Julie: Disability doesn’t define the child. Physical disability doesn’t mean that the child necessarily would be the hard one. From an international adoption standpoint, just because children were diagnosed with that disability in their native country, it doesn’t mean that it would be as bad as what it looks like. The U.S. has so many services and resources, and the change in the kids once they come here is significant.